Attention and Empire's Algorithms

This was a message I shared with First Friends Meeting in Greensboro this past Sunday based in part by the parable of the Good Samaritan found in Luke 10.

Empire's Algorithms

I have been thinking a lot about attention recently. I've been developing a first year class for Guilford students called "Boredom as a Superpower" that looks at ways in which our ability to focus and hold attention is being lost - and of course - how the practice of silence and allowing ourselves to feel bored in order to be more present with ourselves and others is like having superpowers today.

So as it goes, I see attention everywhere.

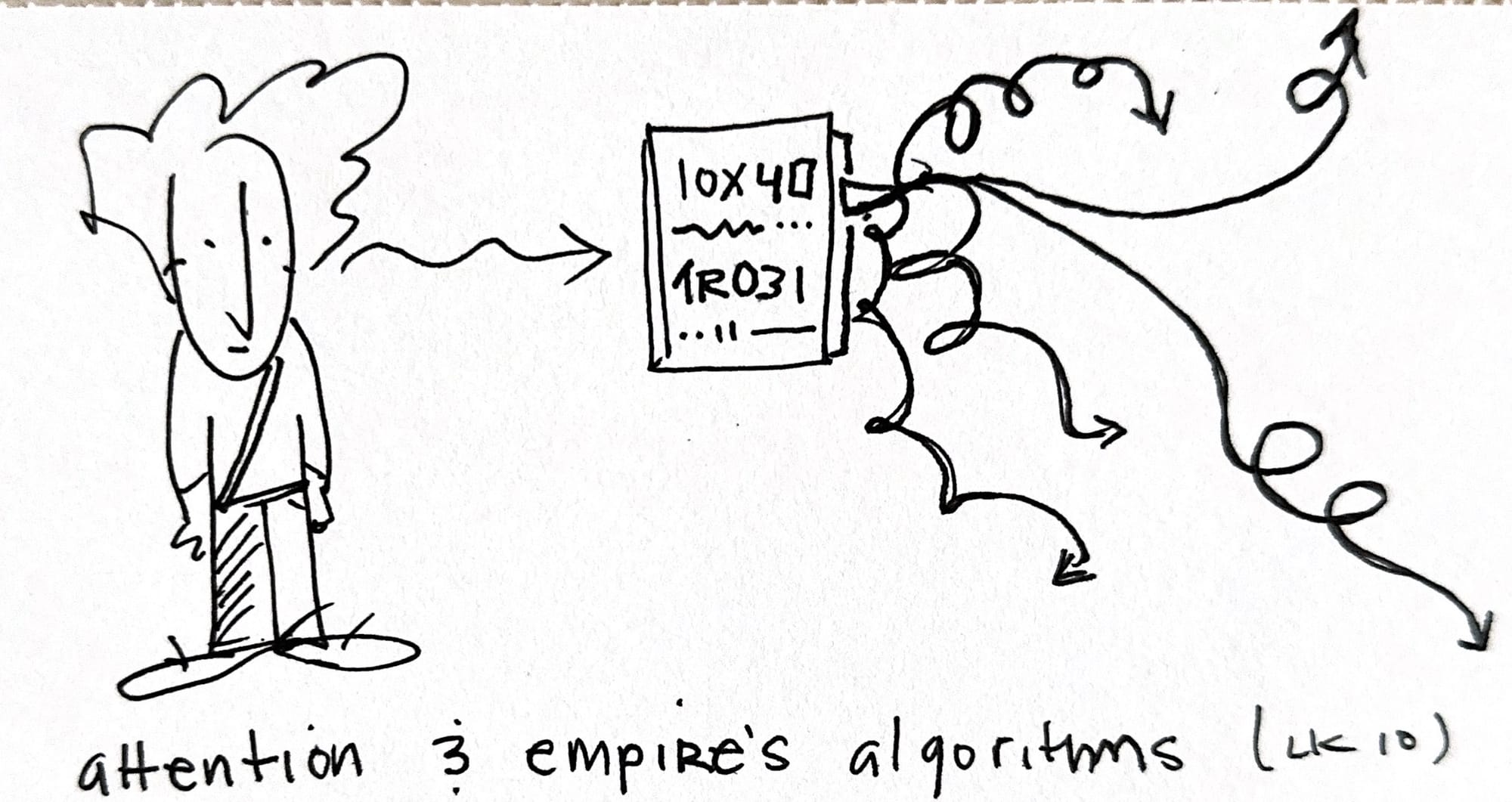

The dominant framework today is one that shapes our attention through constant streams of information served up through algorithms and empire. These algorithms are not trying to serve the betterment of humanity; they’re trying to keep us hooked because it’s good for their bottomline. These things skew what and who we see as human, valuable, and worthy of our concern.

These algorithms aren't just distractions; they're designed to shape us into their values. Values that I think are rooted in wealth for the few, suspicion of others, and stoking fear.

Empire's algorithm wants us to see each other as enemies, as commodities, and as less than human.

But fortunately, we are not powerless against these forces.

When I became a Quaker, my attention shifted. If there are dominant forces that want to shape our attention, then there are traditions and communities that resist those forces.

I would call the Quaker tradition one such community.

Becoming a Quaker in college was part of a longer process of change for me that began when I was 13 and attending Catholic Mass. From that time forward, I was searching for a community I fit within and, in a sense, a pair of spiritual glasses that would help me understand the world and know what to pay attention to (and how to do it).

While it is not the only way and not for everyone, my encounter with the Quaker faith was marked by both a deep sense of “these are things I already knew to be true but didn’t have language for it,” and “this is an entirely new way of seeing myself and the world that is bigger and broader than what I currently have.”

In other words, it confirmed in me some parts and pushed me to grow in others.

This kind of faith spoke deeply to me and has, for the past 24 years, continued to shape how I interpret and see the world. I am here in front of you this morning because I believe that practicing faith in this tradition has the power to change ourselves and the world for the good.

Attention and Suffering

Our text this morning reveals something about what and who we see. Jesus uses the story of the Good Samaritan to illustrate a contrast in attention.

First, you have the man victimized. Robbed. Beaten. Left for dead. While in the story this is an individual, we know that there are many communities in America today who are being terrorized, beaten, and left for dead by empire.

Then you have the Priest and the Levite. These are people of power and privilege. It does not say why they do not see the man who is hurt worthy of compassion, but we know from our own experiences all of the excuses and reasons why this occurs.

The part that always gets me in the story is when it says “and when [each man saw] him, [they] passed by on the other side.”

They saw suffering, and they crossed the street.

They saw, but they did not pay attention.

Maybe they saw but were distracted by things they felt were more important.

They took in information, but they did not encounter the truth of this person’s humanity.

It is easy to imagine these men walking by this man, looking at their phones or pretending not to see while listening to their podcasts with AirPods in.

In either case, they didn't see him as human, as having dignity, as worth their time, or worth caring about.

What's happening in their moral algorithms that enabled them to walk away from a dying person?

Lastly, the Samaritan is shown to pay attention to something deeper and broader. He is one whose spiritual lens enabled a very different kind of action.

The Samaritan is a stand-in for the unlikely hero, the unexpected person, and quite frankly, the one who, if you were the victim, you might not want their help.

As Friends might say, “that name did not occur to me.”

To put a finer point on the subversion of the place the Good Samaritan occupies in society, Clarence Jordan, a farmer and theologian growing up in the segregated south known for his work around racial equity and founding Koinonia Farm, retells this parable as though it took place in Atlanta during segregation.

The man beaten was white. Two white Christian men (a pastor and a worship leader) are the ones who pass him by. And it is an African American man who, when he sees the man beaten lying at the side of the road, is “moved to tears.”

He, whose own reality within society is radically marginalized, is the one who tends to the man whose reality is very likely just a momentary victimization.

What we pay attention to tells us something about what we want to see. What we’re looking for. It tells us something about the shape of our spiritual lenses, and for Jesus and his parable, it is a way of seeing that allows us to be moved to action.

That could be because of a sense of shared responsibility, compassion, practices that shape us over time to pay attention to suffering, or it could be because of one’s suffering or marginalization that keeps us awake to others.

Our Shared Responsibility

This past week, I organized community service work days at Guilford. The idea stemmed from something a Friend said during a business meeting a few months ago, which really stressed the point that Quakers - at least in NC - feel a deep sense of responsibility and care for Guilford. And so if it needs help, make space for folks to help.

That’s a paraphrase, but that’s what I took away from it.

And so this past week, a number of people donated funds and worked to spruce up the welcome center for interested students and their families in the hopes that it will help with recruitment.

We had folks from First Friends, New Garden, Friendship Friends, and college staff show up to put in some hard and hot days.

When asked why he was doing something like this during his summer off from college, a faculty colleague of mine responded, “Guilford belongs to me.”

Guilford belongs to me. Not in ownership, but in love.

I hear echoes of the Samaritan seeing that beaten man and recognizing: this person belongs to me. In solidarity and in love.

I hear this same sentiment from Anne and others about Guilford - it matches a deeper Quaker commitment.

If the algorithms of empire teach us to pass by on the other side, “that’s not my concern,” “that’s not my problem,” then the Quaker algorithm stands in contrast: “we belong one to another and are responsible for the places we are rooted and called.”

- We are the ones responsible for a better world.

- We are the ones responsible for healing the broken.

- We are the ones responsible for feeding the hungry.

- We are the ones responsible for giving compassion to friend and enemy alike.

I came across a funny but somewhat poignant saying from a Quaker elder at our old meeting in Washington who had this cross-stitched in her house:

“If you’re looking for a helping hand, you have no further to look than the end of your own arm.”

I think if we hear this not as an individualized expression, but as a reflection of a certain way of seeing the world, a sense of co-laboring, co-responsibility for what we are creating, a solidarity with those who are struggling, we have come close to the Quaker algorithm of love. It is a commitment to trust that the work we are called to can be accomplished if we pull together and do the work.

Love of God and Love of Neighbor is about a continual process of broadening compassion and solidarity.

God is with those who find ways to expand and deepen love in the world. As Quaker John Woolman once said, “let love be the first motion.”

May it be so among us.

Queries:

- What and who do you see?

- What do you pay attention to? What do you notice?

- How might we keep love and compassion always in front of us, moving us forward?