Write What You See: Standing In The Great Traditions of Resistance (Revelation 1)

I want to share the sermon I preached on April 15, 2023, for the American Friends Service Committee’s annual gathering in Philadelphia. Each year AFSC gathers for business, workshops, and community building. During this time, they have a programmed worship service as a part of their time together. This was the second time I was invited to come and preach at the meeting; the first was in 2014 when we still lived in Camas. It was a lovely experience being with Friends this year, and even better because I was able to take two students to travel in the ministry with me, making the whole trip a valuable and enjoyable experience.

Verses: Revelation 1:9–11 NRSV

“I, John, your brother who share with you in Jesus the persecution and the kingdom and the patient endurance, was on the island called Patmos because of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus. I was in the spirit on the Lord’s day, and I heard behind me a loud voice like a trumpet saying, “Write in a book what you see and send it to the seven churches, to Ephesus, to Smyrna, to Pergamum, to Thyatira, to Sardis, to Philadelphia, and to Laodicea.””

The Two “Projects”

As far back as the biblical tradition goes, there has always been a religion of empire and a religion of liberation and resistance:

Dorothee Soelle, a Feminist Biblical Scholar, put it like this:

“We are participants in one of these two projects: exploitation or fullness of life.” Soelle – The Window of Vulnerability, p14

And in another place, she spoke of what it means to be a participant in the project of the fullness of life, saying:

What I can do in the context of the rich world is minute and without risk in comparison with the great traditions of resistance. The issues is not to venerate heroes but together to offer resistance, actively and deliberately and in very diverse situations, against becoming habituated to death, something that is one of the spiritual foundations of the culture of the First World. – Soelle

It is this point I want to explore: what does it mean for us to see ourselves as a part of the great traditions of resistance, this project both spiritual and social, with an active and deliberate refusal to becoming habituated to death?

We will do this through the lens of three important letters penned by spiritual leaders rooted in this project of life.

John’s Letter

Late in the first century, a poor pastor living under the occupation of the Roman Empire was imprisoned on Patmos, an island used for state prisoners.

We don’t know precisely why John, the author of the letter we know as “The Book of Revelation” today, was imprisoned. Still, we can imagine John’s calling Rome “Babylon” and “the Beast,” saying that it has “become a dwelling place of demons,” and that “the kings of the earth will weep and wail” over Babylon when they see the smoke of her burning, would not go over well with the Romans. Especially because they already had every reason to treat the early church with suspicion because of their refusal to go along with the Roman imperial religion.

John starts his letter from the prison in Patmos:

I, John, your brother who share with you in Jesus the persecution and the kingdom and the patient endurance…because of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus.

John writes to share in the suffering with his people who are also suffering, even when he is far away; this recognition of shared suffering and empathy shapes the letter’s direction. What he shares through the rest of these pages is essentially a pair of spiritual eyeglasses to see through and name the wickedness of empire so that in their suffering, they do not succumb to empire’s siren song.

As you probably know: Apocalyptic literature is a genre used in the biblical tradition to reveal, unmask, and open our eyes to what is going on around us.

John is in prison because he stood in the belief that the kingdom of God is an alternative witness to the Roman empire. For him, Jesus took a stand against empire, and he sees the church being called to stand in that same “testimony.”

In fact, in Revelation 18, one of the most damning critiques of empire anywhere in the whole of the Bible, John writes:

Then, I heard another voice from heaven saying: “Come out of [Babylon], my people, so that you do not take part in [Babylon’s] sins…”

Share in suffering and “Come Out of Empire, My People” are words uttered by prophets both major and minor, long before and long after John: a call I believe remains before Quakers and all people of faith today.

Now you might find it odd that I’m sharing from the book of Revelation with you this morning. Something like the phrase, “Friend, this text would not have occurred to me,” may be running through your head.

But if it really is an anti-imperial text from the first century, as I believe, then you can begin to see why it would be much more advantageous to turn it into a laughing stock and joke of the bible than to take it seriously.

In this letter smuggled out to seven churches, John was concerned with the church assimilating into empire, becoming stagnant, growing rich with power and money, and becoming a stumbling block for the work of liberation in the world.

In the face of this concern, John writes to a marginalized faith community facing the very real and very deadly persecution of empire, to help them know they are not alone and to see what was hidden in front of them.

Staying awake in empire means means survival.

Seeing clearly in empire means knowing who the real enemies are and pulling together even when we suffering.

It means refusing to become habituated to death.

King’s Letter

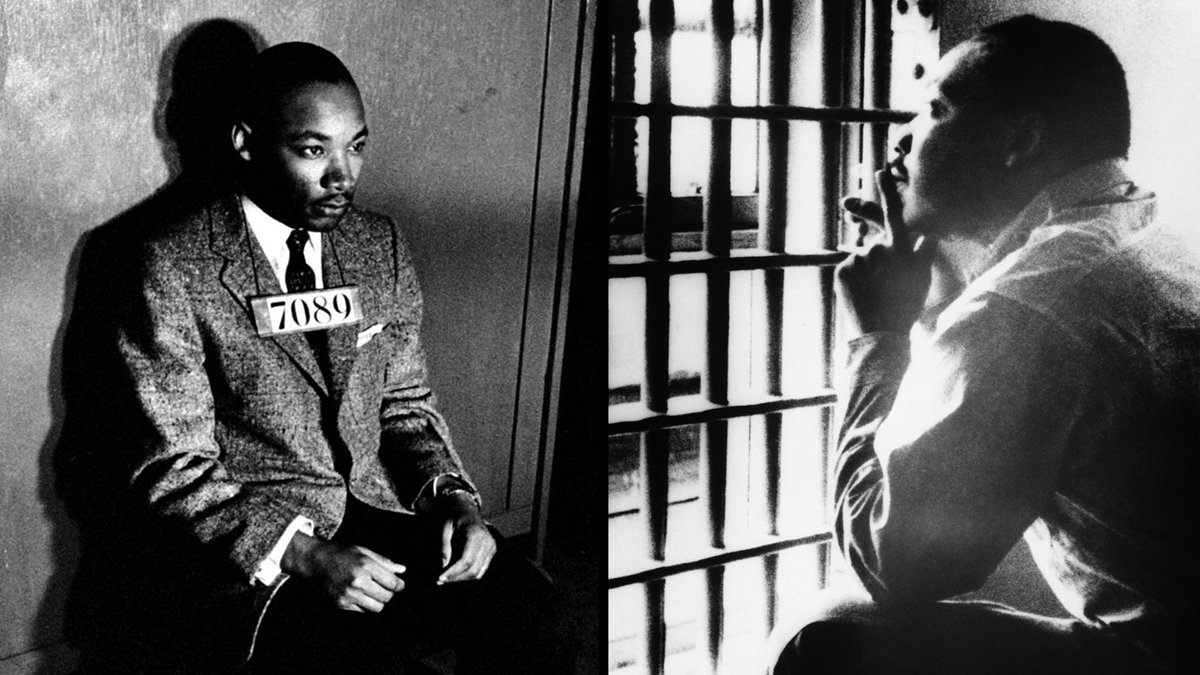

In 1963, there was another letter written. This one smuggled out from a prison in the American South from the pen of an African-American Baptist Preacher and social movement organizer. He too was jailed for being a threat to empire; this time, the reason given was for leading a march of Black protesters without a permit from the city of Birmingham, which had become notorious for its unwillingness to work with their Black citizens and Civil Rights organizations.

In the same way that John the Revelator was himself a prisoner of empire, an agitator of truth, unmasking the evils of Rome, so too Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote in apocalyptic measure, unmasking the intersections of evil that the American empire trades in.

He wrote from a Birmingham prison:

I am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities and states. I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.

Letter from the Birmingham Prison

King’s letter was prompted by a letter from 8 white clergymen from Alabama who wrote criticizing King’s being in Birmingham as an outside agitator. They felt the problem of racism should be handled by local leaders who have knowledge of the situation and handle it through the “proper channels.”

The clergy letter, besides falling out on the wrong side of history, is short, uninspiring, and, well, moderate, as King called it. It’s also an interesting indication of how far that radical anti-imperial gathering of poor people assembled by Jesus and pastored by John the Revelator has come by way of assimilating into the American empire.

King’s letter exposes the hypocrisy of what he called “the white moderate church” because it believes the Gospel has no concern for social issues of the day.

For King, the white (moderate) church has now become a stumbling block for God’s work of liberation for the poor.

King, like John, reaches back to apocalyptic texts and points to the civil disobedience of Shadrach, Meshach, Abednego Jews from the book of Daniel who refused to cooperate with empire (as a sidenote: Daniel is also a favorite text remixed in the book of Revelation).

Then King turns to other examples of people of faith who resisted empire:

- The Prophet Amos.

- Jesus.

- The Apostle Paul.

He names these and others “extremists for love, truth, and goodness.”

On the one hand, King’s letter challenges the white church that has become intertwined with empire, disempowered of critique due to its comfort and riches, while lifting up a picture of those who have, throughout time, taken a stand against empire in the name of the God they worship.

His imprisonment in Birmingham was the result of his “active and deliberate resistance against becoming habituated to death.”

His letter is a reminder to those faith communities the dangers of losing the way and, instead of standing rooted in the spiritual traditions of resistance, becoming an accomplice and beneficiary of empire.

King wrote:

Human progress never rolls in on the wheels of inevitability; it comes through the tireless efforts of [people] willing to be co-workers with God, and without this hardwork, time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation (86).

King, in his letter, like John’s before it, invites his readers to see fully the spiritual ramifications of siding with empire in the hopes that his readers will choose to stand instead in the tradition of resistance that has knit these communities of faith together over time.

Seeing fully means standing with those whose backs are against the wall.

It means being willing to give up power, luxury, and relative comfort for a greater cause.

And refusing to become habituated to death.

Fox’s Letter

If you’ll indulge me, I want to close our time together with one last letter.

This letter comes from Doomsdale.

No, it’s not a chapter from the LOTR trilogy.

It comes from George Fox, one of the founders of the Quaker tradition.

Fox was no stranger to imprisonment, and in 1656 because he refused to take off his hat in court, and found himself in a prison, he called Doomsdale.

You can probably guess by the name that Doomsdale was not a charming place.

Describing the conditions of the Lancaster prison, Fox said that human excrement went up to the top of their shoes, filling the chambers with a stench that made breathing difficult and sleeping an almost impossible task. When Quakers smuggled in straw for the prisoners to burn to help mask some of the smell, the jailer became so enraged, as Fox reports, that he took “pots of excrement from the thieves and poured them through a hole upon our heads.”

Impressively, Fox was there nine weeks in all and believed that while in prison, he was able to spread the light of God in Cornwall.

What you may not know is that the letter from this time, smuggled out by Quakers aiding those imprisoned, is the source of some of the most beautiful words found in the Quaker tradition:

…be patterns, be examples in all countries, places, islands, nations, wherever you come; that your life and conduct may preach among all sorts of people, and to them. Then you will come to walk cheerfully over the world, answering that of God in everyone; whereby in them you may be a blessing, and make the witness of God in them to bless you.

George Fox – Lancester 1656

What I find interesting about this, besides the juxtaposition of content and context, is how the rest of this letter, like John’s and King’s, is a letter of resistance, unmasking empire, helping the early Quaker readers see clearly what is going on around them.

I am going to read a longer excerpt. I imagine some of this will be a surprise to you, especially if you’ve never heard any of Fox’s writings at length before, but I want you to listen to the way in which Fox describes the two paths, the two religions, the religion of empire and those who offer an alternative witness:

Reign and rule with Christ, whose scepter and throne are now set up, whose dominion is over all to the ends of the earth; whose dominion is an everlasting dominion, his throne an everlasting throne, his kingdom an everlasting kingdom, his power above all powers. Therefore this is the word of the Lord to you all, “Keep in the wisdom of God,” that spreads over all the earth; the wisdom of the creation that is pure from above, not destructive…For all the princes of the earth are but as air to the power of the Lord God, which you are in and have tasted of. Therefore live in it, that is the word of the Lord God to you all. Do not abuse it; keep down and low; and take heed of false joys, that will change. Bring all into the worship of God. Plough up the fallow ground.

And then, shortly after this, we get the earlier passage I read.

These letters lead me to ask:

Friends, are we:

“Keep[ing] in the wisdom of God,” – the wisdom of the creation that is pure from above, not destructive.

Have we learned to:

not abuse [our power, our standing]; keeping down and low; and taking heed of false joys, that always change.

Are we entering into suffering and solidarity with those whose backs are against the wall?

Those whose own lives are being crushed, scapegoated, and lynched by empire?

Are we with our lives resisting empire standing up as:

…patterns, …examples in all countries, places, islands, nations, wherever you come; that your life and conduct may preach among all sorts of people, and to them.

Fox, with a deeply spiritual analysis, is able to see and name these two ways of exploitation or fullness of life.

May it be so with us here today as well.

Thank you, Friends.

Query:

- Do we see ourselves here?

- What do we need to draw on the spiritual resources of this tradition?

- How do we not only stand within it but help to carry it forward?

A Benediction:

From George Fox’s Letter:

Therefore you that be chosen and faithful, who are with the Lamb, go through your work faithfully in the strength and power of the Lord, and be obedient to the power; for that will save you out of the hands of unreasonable men, and preserve you over the world to himself. Hereby you may live in the kingdom that stands in power, which has no end; where glory and life is.